Thomas Scheibitz

18 Sep - 01 Nov 2014

Thomas Scheibitz

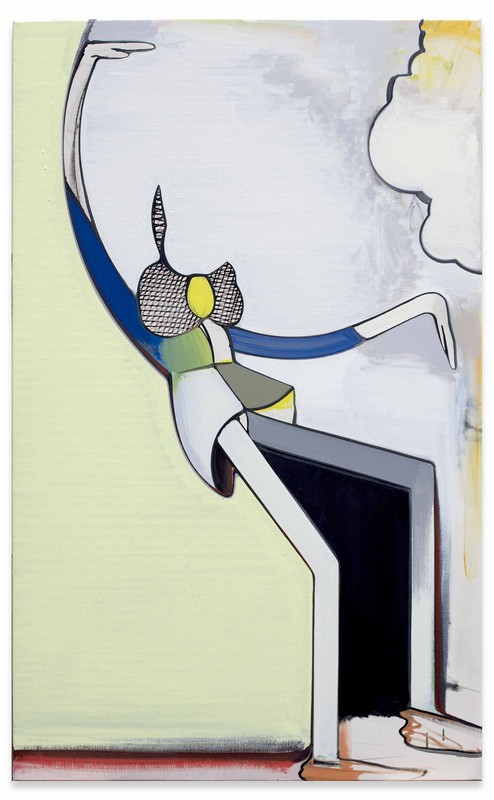

Der Honigdieb, 2014

Oil, vinyl, lacquer, pigment marker on canvas

180 x 90 cm

70 7/8 x 35 3/8 inches

© Thomas Scheibitz / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2014

Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London

Der Honigdieb, 2014

Oil, vinyl, lacquer, pigment marker on canvas

180 x 90 cm

70 7/8 x 35 3/8 inches

© Thomas Scheibitz / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2014

Courtesy Sprüth Magers Berlin London

Thomas Scheibitz

Radiopictures

18/09/14 - 01/11/14

Already in the title of the exhibition Radiopictures, Thomas Scheibitz demonstrates that his artistic

thinking, in addition to tectonics, scale, and proportion, also revolves around time-based media:

music, film, text. Temporal aspects, such as simultaneity and continuum, are for him further

dimensions of composition.

The title of the painting Historische Szene (Historical Scene) awakes associations with theatre and

film. The depicted scenery could be a film set or a stage, aiming at the liminal experience of an

ambiguous state between various layers of reality – an “open field” which can repeatedly be found in

Scheibitz’s work and in which constructions dissolve into their tectonic structures. The same is

applicable to his painting Gasthof Ravoux (Ravoux Inn), whose title, in the first instance, still refers

to the inn in which Van Gogh stayed during the last three months of his life. Here architecture

begins to unravel, combining itself with typographic elements, drifting over facial features,

confronted by alarming colours, and bobbing almost like an airship on a blue-grey ground. That

such unequivocal associations may not be intended, is also evident in the work Spiegelwolke (Mirror

Cloud): the cloud-like structures to the left of the pictorial field, in combination with a circular area,

the left bottom margin of which features a “nose of paint” and a smaller circle hovering above it,

become the tears from a head bowed in sorrow, but which could at the same time be a planet above

a mountain peak, to which an ox-blood coloured road leads: the genres of landscape and portrait

painting combine in a non-figurative composition of colours, forms, and planes.

The title Der Honigdieb (The Honey Thief), with its associations (“Honigdieb” appearing in

Scheibitz’s and the German title of Cranach’s painting, meaning “honey thief”) to the painting Venus

mit Armor als Honigdieb (Cupid complaining to Venus) by Lucas Cranachs the Elder, again

references a specific art historical example, without actually depicting a clearly perceptible figure.

The title Grammatik (Grammar) alludes to a form of systemization which plays a role in linguistics as

much as it does as a pictorial paradigm in art history. Each painting generates its own storyboard

that has telescoped into an image.

In the diamond paper publication Details I, accompanying the exhibition, Scheibitz illustrates the

process of a mindful wandering across details. The pictorial compositions are characterised by a

shimmering, flickering, pulsating of details, individual elements, structures, and materials, conveying

weightlessness as well as mobility. Scheibitz’s gaze focuses on the continual, virtually restless,

iconographic-iconological reorientation underway at present, and simultaneously on the discovery of

formal ideas reflected in the zeitgeist, which will still outlast it. Nevertheless no detail stands for a

crystallized definition of a notion, no composition represents a narrative. Scheibitz does not permit a static regime of meaning to emerge, he finds any proximity to ideology suspect. Instead he asks for

example: is the form derived from an everyday object already art, or an element of design for the

mass market? Can the same approaches to compositional analysis be used for both? Are the two

modes of interpretation perhaps based on the same design principles?

In order to find out, Thomas Scheibitz dissects details of the visible world as well as his own works

into fragments, examining the individual components – transferring them like individual words,

graphemes, phonemes, morphemes, lexemes into his visual language. He relocates them to his

very own world of hue and form, to be neither categorised there as abstract nor figurative. Similarly

to processes of encryption, information is divided. In doing so, Scheibitz values chance, not only as

a testing apparatus, but also as a generator of cognitive dissonance. Ultimately however his

drawings, photographs, paintings, and sculptures culminate in extremely precise analyses of such

factors as expectation, attitude, and experience, which also inform his own gaze. He interrogates

such structures, disassembles the interpretational schema, organises the elements as if in a

periodic system, recomposes them, tests arrangements, and employs the most differing

mechanisms of selective emphasis, accentuation, and attribution.

Thomas Scheibitz‘s works function, in this manner, like the concealed sources of sound or the cut

ups, which William S. Burroughs recommended in his essay The Electronic Revolution (1970) to

instigate a revolution: the found components are extracted from the seemingly obvious fabric of

meaning; the viewer’s fundamental notions, unconsciously received and pre-defined in terms of both

emotions and norms, become corrupted; context and its functional modes are subversively

undermined. Burroughs opposed conditioning generated by word-image or word-word

combinations, which like a virus manipulates the thinking of the individual and which is misused by

ideologues. Scheibitz is also wary of any form of narrative and attendant viral infiltrations. He seeks

a visual language which immunises him, as well as the recipients of his works, against such viruses,

thus enabling emancipation.

Thomas Scheibitz (*1968, Radeberg, Deutschland), studied at University of Fine Arts of Dresden

and lives and works in Berlin. Recent solo shows have been held at BALTIC Centre for

Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2013) and MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main

(2012). Most recent group shows include BubeDameKönigAss Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin (2013),

One Foot in the Real World at Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2013), Das doppelte Bild at

Kunstmuseum Solothurn (2013), as well as Fruits de la Passion at Centre Pompidou, Paris (2013)

and Don't be Shy, Don't Hold Back at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2012).

Radiopictures

18/09/14 - 01/11/14

Already in the title of the exhibition Radiopictures, Thomas Scheibitz demonstrates that his artistic

thinking, in addition to tectonics, scale, and proportion, also revolves around time-based media:

music, film, text. Temporal aspects, such as simultaneity and continuum, are for him further

dimensions of composition.

The title of the painting Historische Szene (Historical Scene) awakes associations with theatre and

film. The depicted scenery could be a film set or a stage, aiming at the liminal experience of an

ambiguous state between various layers of reality – an “open field” which can repeatedly be found in

Scheibitz’s work and in which constructions dissolve into their tectonic structures. The same is

applicable to his painting Gasthof Ravoux (Ravoux Inn), whose title, in the first instance, still refers

to the inn in which Van Gogh stayed during the last three months of his life. Here architecture

begins to unravel, combining itself with typographic elements, drifting over facial features,

confronted by alarming colours, and bobbing almost like an airship on a blue-grey ground. That

such unequivocal associations may not be intended, is also evident in the work Spiegelwolke (Mirror

Cloud): the cloud-like structures to the left of the pictorial field, in combination with a circular area,

the left bottom margin of which features a “nose of paint” and a smaller circle hovering above it,

become the tears from a head bowed in sorrow, but which could at the same time be a planet above

a mountain peak, to which an ox-blood coloured road leads: the genres of landscape and portrait

painting combine in a non-figurative composition of colours, forms, and planes.

The title Der Honigdieb (The Honey Thief), with its associations (“Honigdieb” appearing in

Scheibitz’s and the German title of Cranach’s painting, meaning “honey thief”) to the painting Venus

mit Armor als Honigdieb (Cupid complaining to Venus) by Lucas Cranachs the Elder, again

references a specific art historical example, without actually depicting a clearly perceptible figure.

The title Grammatik (Grammar) alludes to a form of systemization which plays a role in linguistics as

much as it does as a pictorial paradigm in art history. Each painting generates its own storyboard

that has telescoped into an image.

In the diamond paper publication Details I, accompanying the exhibition, Scheibitz illustrates the

process of a mindful wandering across details. The pictorial compositions are characterised by a

shimmering, flickering, pulsating of details, individual elements, structures, and materials, conveying

weightlessness as well as mobility. Scheibitz’s gaze focuses on the continual, virtually restless,

iconographic-iconological reorientation underway at present, and simultaneously on the discovery of

formal ideas reflected in the zeitgeist, which will still outlast it. Nevertheless no detail stands for a

crystallized definition of a notion, no composition represents a narrative. Scheibitz does not permit a static regime of meaning to emerge, he finds any proximity to ideology suspect. Instead he asks for

example: is the form derived from an everyday object already art, or an element of design for the

mass market? Can the same approaches to compositional analysis be used for both? Are the two

modes of interpretation perhaps based on the same design principles?

In order to find out, Thomas Scheibitz dissects details of the visible world as well as his own works

into fragments, examining the individual components – transferring them like individual words,

graphemes, phonemes, morphemes, lexemes into his visual language. He relocates them to his

very own world of hue and form, to be neither categorised there as abstract nor figurative. Similarly

to processes of encryption, information is divided. In doing so, Scheibitz values chance, not only as

a testing apparatus, but also as a generator of cognitive dissonance. Ultimately however his

drawings, photographs, paintings, and sculptures culminate in extremely precise analyses of such

factors as expectation, attitude, and experience, which also inform his own gaze. He interrogates

such structures, disassembles the interpretational schema, organises the elements as if in a

periodic system, recomposes them, tests arrangements, and employs the most differing

mechanisms of selective emphasis, accentuation, and attribution.

Thomas Scheibitz‘s works function, in this manner, like the concealed sources of sound or the cut

ups, which William S. Burroughs recommended in his essay The Electronic Revolution (1970) to

instigate a revolution: the found components are extracted from the seemingly obvious fabric of

meaning; the viewer’s fundamental notions, unconsciously received and pre-defined in terms of both

emotions and norms, become corrupted; context and its functional modes are subversively

undermined. Burroughs opposed conditioning generated by word-image or word-word

combinations, which like a virus manipulates the thinking of the individual and which is misused by

ideologues. Scheibitz is also wary of any form of narrative and attendant viral infiltrations. He seeks

a visual language which immunises him, as well as the recipients of his works, against such viruses,

thus enabling emancipation.

Thomas Scheibitz (*1968, Radeberg, Deutschland), studied at University of Fine Arts of Dresden

and lives and works in Berlin. Recent solo shows have been held at BALTIC Centre for

Contemporary Art, Gateshead (2013) and MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main

(2012). Most recent group shows include BubeDameKönigAss Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin (2013),

One Foot in the Real World at Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin (2013), Das doppelte Bild at

Kunstmuseum Solothurn (2013), as well as Fruits de la Passion at Centre Pompidou, Paris (2013)

and Don't be Shy, Don't Hold Back at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2012).